Why Self-Control Fails & What Psychology Tells us About Making it Work

Understanding the psychology of impulse, resistance & what really helps us change

This post has been inspired by

We all know what we should do: Go to bed earlier, say no to the third biscuit, focus on the task instead of scrolling. And yet, the gap between knowing and doing often feels like a canyon. Perhaps, that’s because self-control (something we tend to think of as sheer effort or grit), turns out to be far more complex than just resisting temptation.

You see, people with the highest levels of self-control often don’t feel like they’re resisting anything at all. They’ve learnt that self-control isn’t a battle of will, but a reflection of how well we understand ourselves.

Psychological research increasingly supports this shift in perspective. What was once thought of as a depletable resource is now seen more as a matter of attention, motivation, and structure.

So why do we struggle?

Because most of our self-control efforts focus on suppression, rather than (self) understanding.

So, let’s begin by understanding what’s really happening beneath the surface.

What Self-Control Really Is

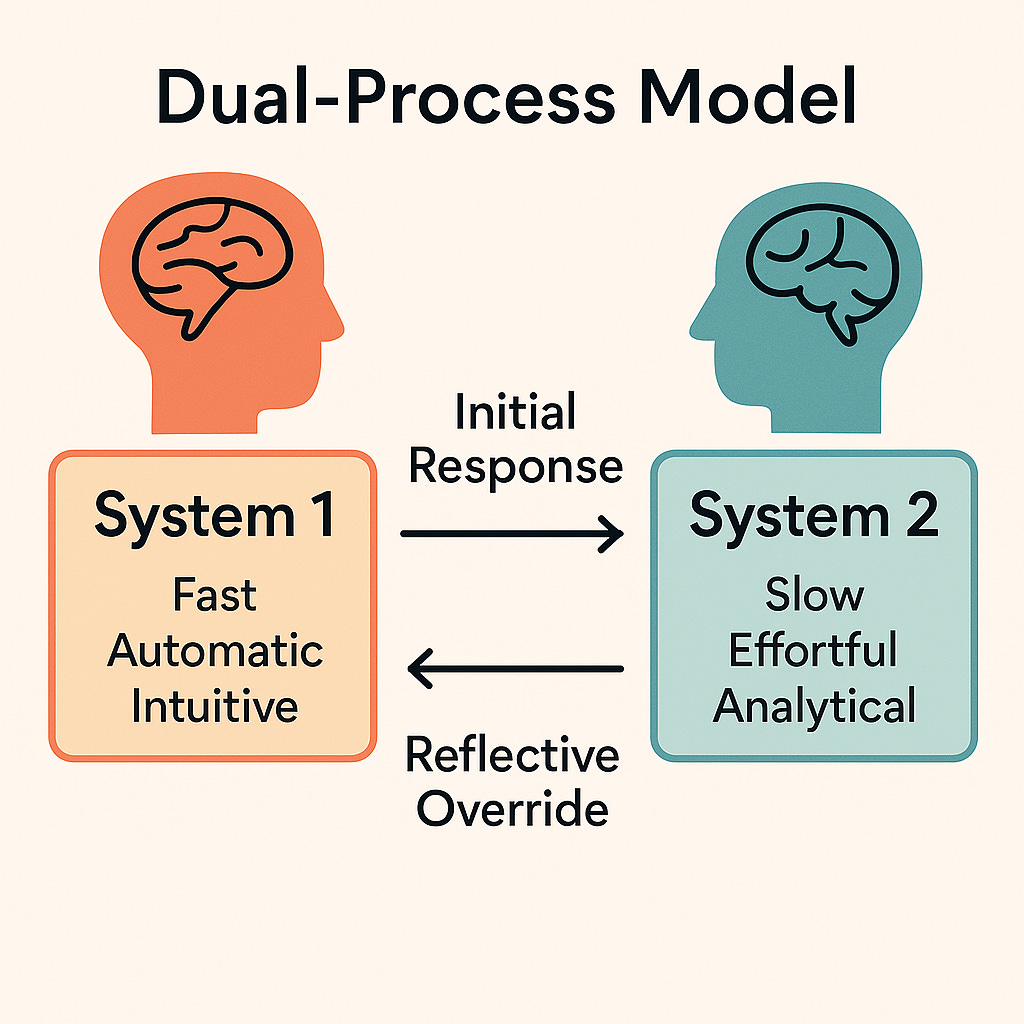

Behind every act of self-control is a negotiation between competing systems in the mind. In psychology, we often describe this through dual-process models: One system is fast, automatic, and emotionally driven. The other is slower, more reflective, and deliberate. So, when I reach for the third biscuit, or for my phone without thinking, it’s not because I’m weak. It’s because the impulsive system (system 1) is built to act first.

Self-control, then, becomes the ability to pause. To notice the urge without automatically following it. And this is more than just momentary inhibition. This ‘noticing’ involves regulation too: the ability to align present actions with longer-term goals or values, even when short-term desires pull us elsewhere!

For a long time, ideas like ‘ego depletion’ suggested that self-control functions like a muscle, one that gets tired the more we use it. For example, after resisting a temptation earlier in the day, we might be more likely to give in to the next one because our willpower has been “used up.”

We Don’t Run Out of Self- Control

Recent research, however, challenges this view. Proposing that instead of depletion, what happens is a shift in motivation and attention. In other words, we don’t run out of self-control, we start caring about different things.

When we are tired, under pressure, or emotionally drained, our focus narrows to whatever feels most immediately rewarding, like staying in bed, checking our phone, or avoiding a task altogether.

Haven’t we all been there?

In those moments, the more effortful choice no longer feels worth it, even if it aligns with our deeper goals. The problem is not a lack of willpower. It is that our attention and motivation have shifted toward short-term relief instead of long-term values.

Rather than excusing our lapses, understanding self-control this way explains them, and in the process, we find something more useful than blame. That is the chance to approach ourselves with curiosity, and to build strategies that work with the mind, not against it!

Why Self-Control Often Fails

This tells us that self-control doesn’t fail in a vacuum.

It fails in context: when we’re tired, distracted, emotional, or simply caught off guard. Every act of ‘resisting’ takes place in a world full of internal and external noise.

In a well-known study, Hofmann and colleagues gave participants smartphones and contacted them seven times a day for a week. Each time, participants answered a series of questions about their current experience. Were they feeling a desire? What was the desire for? Did it conflict with one of their personal goals? Had they tried to resist it, and had they succeeded?

The findings revealed a clear pattern: desires are frequent and resisting them often falters under pressure. On average, participants experienced a desire every few hours, often without full awareness. And whether or not they resisted their desires had less to do with willpower, and more to do with the demands of the moment.

Not a Lack of Effort

Resisting impulses was harder when people were stressed, busy, mentally tired, or when the desire had social cues attached to it, like when others around them were indulging.

Interestingly, those presenting higher self-control didn’t report ‘resisting’ more often. Instead, they reported fewer internal conflicts to begin with! So, rather than fighting temptation, they had designed their routines in a way that reduces tempation’s grip, by building habits, or avoiding known triggers.

This indicates self-control often fails not from a lack of effort, but from an overload of competing pressures. Like so, the lesson is not to push harder, but to pay closer attention to: emotional states, thought patterns and the environments that influence our impulses to begin with.

What Strengthens It

If self-control often falters under pressure, then strengthening it is less about gritting our teeth and more about adjusting how we live and respond to life.

The findings by Hofmann and colleagues points us toward something subtle but crucial. Self-control grows not through force, but through design.

One part of that design is self-awareness. Identifying the early signs of desire and the moment it begins to conflict with our intentions allows us to respond rather than react. Another part is shaping our environment so that fewer temptations arise at all. Small changes in routine or surroundings can remove the need for constant restraint.

Even a brief pause can shift the outcome, as it creates space to reconnect with our goals. Success is not always about suppression. It can mean learning from the urge, noticing what triggered it, and preparing differently next time.

Therefore, self-control becomes stronger when we create conditions that support it. And those conditions are often intentional, and built in advance.

Closing Thoughts

Self-control is not a matter of brute strength. It’s a matter of understanding. Of recognising how the mind moves, how context influences behaviour, and how small changes can make ‘resisting’ less necessary in the first place.

We’re inclined to think of lapses as failures, but they are information.

They show us where our strategies (or lack of) bend, where our needs press forward, and where our habits could do more of the work. What strengthens self-control is hardly a revelation. It’s simply that moment before saying no. The moment we arrange our time, our space, our attention.

In learning to work with ourselves rather than against ourselves, we stop chasing the ideal of perfect discipline. And we begin something far more sustainable.

Living in line with what we envision, even when desire pulls us elsewhere.

References

Duckworth, A. L., Gendler, T. S., & Gross, J. J. (2016). Situational strategies for self-control. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(1), 35–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615623247

Hofmann, W., Baumeister, R. F., Förster, G., & Vohs, K. D. (2012). Everyday temptations: An experience sampling study of desire, conflict, and self-control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(6), 1318–1335. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026545

Inzlicht, M., Schmeichel, B. J., & Macrae, C. N. (2014). Why self-control seems (but may not be) limited. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 18(3), 127–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2013.12.009

de Ridder, D. T. D., & Gillebaart, M. (2013). Impulse and self‑control from a dual‑systems perspective. Journal of Personality, 81(3), 507–517. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12034

Self control and the strategies you pointed out are struggles that everyone can relate to. And I really liked how you summarized in the end that it's the conditions that have to be intentionally enforced before hand to be able to make the tasks for long-term goals easier. Like how it's always easier to work in an office than at home. Bcz subconsciously our mind registers home as a place of rest and enjoyment.

Thank you Dom for this post.

It was Nice to read Dom, Takeaway, self control isn’t a battle of will, but a reflection of how well we understand ourselves. Self-control grows not through force, but through design. Thanks you and do have a good one!!!