Resilience

How to adapt to and grow stronger from adversity.

We tend to think of resilience as the ability to bounce back, but in psychology we know that resilience entails more than that: it entails the capacity to adapt, recalibrate, and even grow through difficulty.

Ancient wisdom has long recognised this quality.

Buddhism, for example, teaches that adversity can be a path to adaptability, strength, and clarity. Today, research in neuroscience and psychology increasingly corroborates this insight, showing the capacity of our brains and bodies for resilience.

In this collaborative post, I will explore the inner neuropsychological mechanisms that underpin resilience, while Promise will draw from his Buddhist and wellness background to show how these mechanisms can be nurtured in everyday life so that adversity feels less depleting and more energizing.

To begin, let’s look at a core system that drives our response to stress.

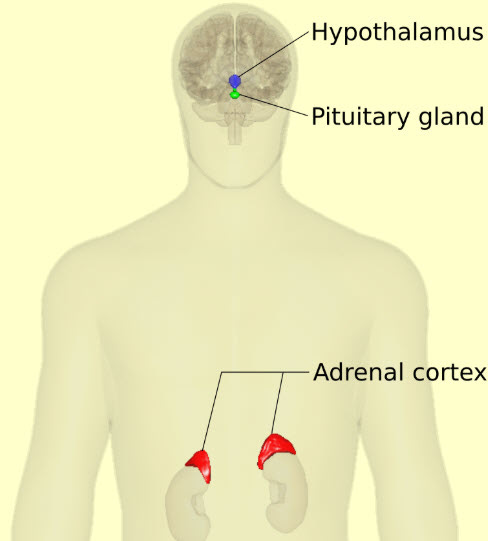

The HPA Axis

At the centre of the body’s response to challenge is the HPA axis (the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis), a system that mobilises us when we encounter stress. The hypothalamus signals the pituitary, which in turn signals the adrenal glands to release (primarily) cortisol, preparing the body for action.

There was a time when action meant running from predators. Nowadays it means meeting deadlines, handling awkward conversations, or navigating daily pressures that demand focus and energy. We all know that stress too well!

For a resilient mind, the key is that the HPA axis recalibrates once the immediate challenge has passed. Recalibration entails the system returning to baseline efficiently. That is the fall of cortisol levels, stabilisation of heart rate, and restoration of energy. Because, when recalibration falters, stress responses can remain elevated and leave the body in a state of wear and tear.

This is where adaptation and balance begin, in this regulation, when the stress response fulfils its role of mobilising us to face demands without becoming prolonged.

Each surge of stress is not a problem in itself.

Cumulative Wear and Tear

Problems arise when activation states become the default, that is when the body never quite resets. This generates a cumulative wear and tear known as allostatic load. You see, elevated cortisol that stick around too long can affect sleep, mood, and even memory.

Over time, rather than preparing us, it drains us.

HPA axis recovery is therefore as important as its activation. When the nervous system can settle, when cortisol falls and balance is restored, stress becomes a strengthening force rather than a corrosive one.

Resilience lives in this cycle: the capacity to engage fully with challenge, then return to equilibrium so the system is ready for what comes next.

Still, resilience is not only about how the body responds to and regulates stress, but also about how we interpret it. The meaning we give to an experience can either amplify stress or help us manage it.

Body and Mind

How we assess our experiences feeds directly into the HPA axis: when we interpret a situation as overwhelming, the stress response surges more strongly and takes longer to settle. When we see the same situation as challenging but manageable, activation is more measured, and recovery comes faster.

In psychology we call this process appraisal.

Note that interpretation is not about denying difficulty, but about perspective.

You and I can face the same event and react in completely different ways, not because our bodies respond differently at first, but because our minds frame the situation differently. So, when our interpretations are flexible, when we can go from seeing an obstacle as a threat to seeing it as a problem to be solved or endured, resilience grows.

This simplified explanation shows how resilience unfolds from body to mind and mind to body. The HPA axis equips us to respond to stress, its recovery protects us from the wear of allostatic load, and our interpretations of the ups and downs of life influence whether stress becomes amplified or contained.

Resilience therefore rather than entailing shutting stress down entails working with it, allowing activation, recovery, and perspective to form a cycle that supports adaptation and growth.

How we nurture these processes in daily life is where the science of resilience greets the wisdom of practice. 1

This is where Promise will continue

Healthy Living

Our capacity to take on life’s challenges has a lot to do with our vitality, and our vitality has a lot to do with our daily habits.

Quality sleep allows our brain to process emotional experiences, balance hormone levels, and prepare our mind for the day. Whole plant foods lower inflammation and keep our immune system strong. Physical exercise lifts our mood and boosts our confidence. Strong relationships elevate us and bring meaning to our life. And last but not least, meditation reduces stress and makes our mind more flexible.

These habits have been shown in peer-reviewed scientific literature to help us prevent, manage, and reverse most chronic diseases. The reason, proposed by Lifestyle Medicine pioneer Dr. Dean Ornish, is that most chronic diseases share underlying biological processes — an overactivation of our sympathetic nervous system, oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, changes in gene expression, a dysregulation of our microbiome, and a shortening of our telomeres — all of which are counteracted by healthier lifestyle choices.

Better yet, sleeping well, eating whole plant foods, moving more, loving more, and meditating also improve our mental health, as shown by the promising field of Lifestyle Psychiatry, and help us live long, as shown by Dan Buettner’s epidemiological longevity studies.

The healthier our lifestyle, the less our life force is busy repairing self-inflicted damage, and the stronger and more resilient we become to navigate life’s challenges.

The Relaxation Response and Open Awareness

Dom introduced us to the stress response. At the beginning of the 20th century, physiology researcher Walter Bradford Cannon studied the stress response at Harvard Medical School and called it the “fight-or-flight response”. Decades later, in the same Harvard room, cardiologist Herbert Benson studied its opposite — the relaxation response.

The relaxation response recalibrates our HPA axis. It entails a decreased activity of our sympathetic nervous system and an increased activity in our parasympathetic nervous system. Our blood pressure goes down. Our metabolism, heart rate, respiratory rate, and brain waves all slow down. We are more at ease. We think more clearly.

Although this relaxation response naturally occurs under certain conditions, Benson observed that it can also be deepened through specific practices. When studying relaxation techniques such as breath meditation, mantra meditation, prayer, and progressive muscle relaxation, Benson concluded that the active ingredients behind all of them were

a quiet environment,

a comfortable position,

repetition, and

a passive attitude toward thoughts.

I will give you a technique to elicit this relaxation response in a bit.

On a similar theme, another interesting area of study is neurofeedback researcher Dr. Les Fehmi’s “Open Focus”. When Fehmi measured people’s brain waves, he noticed that their “attentional style” — not what they attended to but how they attended — was directly linked to their brain wave patterns.

Fehmi observed that our default, narrow form of attention produces beta brain waves and stress. Meanwhile, an open, diffused, all-inclusive attention with no particular object produces alpha brain waves and wellbeing — especially when one lets go of the perception of separation between self and the world.

Cultivating this open, immersed awareness with the help of his neurofeedback equipment, Fehmi felt “more open, lighter, freer, more energetic and spontaneous” — and so did his clients.1

As a former Buddhist monk, I can affirm that Gotama the Buddha described the same observations as these two researchers twenty-five centuries ago.

So how can you, in your daily life, cultivate this relaxation response and open awareness?

Please try this technique: in a quiet place, sit down or lie down. Keep your back straight, your whole body relaxed, your mouth closed, and a gentle smile on your lips and eyes. Keep your attention open and light. Gently feel the sensations of your breath naturally coming in and out. Stay in the flow of the natural breath, without contracting your attention or controlling the breath. Allow your breath to naturally go deep into the belly and slow down by itself, especially the out-breaths. Once your attention is in the flow of the breath, open your mind fully to the present moment.

Be aware of:

All sounds — whether coarse or subtle,

All sights — by relaxing your gaze and opening your peripheral vision, and

All sensations — whether pleasant, neutral, or unpleasant.

And let everything be. Let everything flow naturally.2

Once you are successful practicing this technique in a quiet environment, you can also use it in the middle of your daily activities.

This type of relaxed, open awareness makes us more resilient in the face of pain. When neuroscientists compared how untrained subjects and trained meditators experience physical pain, they observed that meditators show a clear decrease in

pre-stimulus anticipation — “Oh no, I’m about to experience something unpleasant!”,

intra-stimulus resistance — “I hate this!”, and

post-stimulus rumination — “That was horrible!”,

the three components of what psychologists call “pain catastrophizing”.3

With an open and light awareness, our pain remains but our suffering dissolves.

Wise Stress Exposure

Once we live a healthy lifestyle and know how to relax, we have the perfect ground to make the best use of stress.

The word “stress” comes from the Latin “stringere”, meaning “to pull” or “to stretch”, and the same challenges that can tear us apart when excessive can also stretch us toward growth when wisely applied. Stress is then known as

eustress — from the Greek “eu” meaning “good”, or

hormetic stress — from the Greek “hormáein” meaning “to set in motion” or “to excite”, since such a wise exposure to stress sets in motion processes that end up making us stronger.

This capacity not only to adapt to but also to grow from adversity is intrinsic to all forms of life — philosopher Nassim Nicolas Taleb calls it “antifragility” — and you can harness it to your advantage.

Here is how:

Let go of your fixed ideas about who you are and adopt a growth mindset. As a living being, you can grow, you can expand, you can become stronger.

Go to the edge of your current comfort zone but without hurting yourself. This could mean doing pushups in the morning, taking a cold shower, visiting a new country, learning a new language, or putting yourself in a socially stressful situation. The key is to safely seek discomfort.

Mentally associate your exposure to stress to a noble cause, such as becoming healthier and helping others. As Dom pointed out, cognitively appraising stress as beneficial is key.

Give your body and mind the time they need to recalibrate and grow stronger from the stress, expanding your comfort zone.

Return to step 2, push a bit further, and keep going.

In summary, life is resilience, and when we increase our life force — through healthy living, open awareness, and wise stress exposure — we become more resilient

Reference List Dom’s Section :

Christensen, D. S., Garde, A. H., Rugulies, R., Hjortskov, N., Prescott, E. I., Svane-Petersen, A. C., & Hansen, Å. M. (2022). Sleep and allostatic load: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 62, 101592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2022.101592

de Lima, D. (2024). What Makes a Resilient Mind? Tiny Brain.

James, A. L., Lawrence, C., de Boer, S. F., & Joëls, M. (2023). Understanding the relationships between physiological and psychosocial stress, cortisol and cognition. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 14, 1085950. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1085950

O’Byrne, J. N., De Bodman, C., & Boisseau, N. (2021). Sleep and circadian regulation of cortisol: A short review. Current Opinion in Endocrine and Metabolic Research, 17, 100307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coemr.2021.100307

Fehmi, L. G. (2003). Attention to attention. In J. Kamiya (Ed.), Applied neurophysiology and EEG biofeedback. Future Health, Inc.

For detailed guidance, see Three Magic Breaths

Goleman, D., & Davidson, R. J. (2017). Altered traits: Science reveals how meditation changes your mind, brain, and body. Avery.

Thank you, Promise, for proposing this collaboration! It's been such a pleasure to bring our perspectives together. I’ve truly enjoyed seeing how your teaching translates these ideas into something so grounded and accessible <3

I really enjoyed this post, and I love how coming at the same topic from two perspectives creates something that's greater than the sum of its parts. It's especially encouraging to think we can exercise our resilience through stimulation and rest, just like physical strength training.