Why Trying Not to Think of Something Makes You Think of It Even More

The Psychology of Suppression & Thought Rebound

There’s a role in my life I’m very proud of: I’m an aunt. Not just any aunt by the way, but the kind that gets a call late at night because my fifteen-year-old nephew needs to talk through his problems.

Recently, he rang me during a sleepless night. He told me he was trying desperately to get something out of his head, but the more he tried not to think about it, the stronger the thought came back.

Haven’t we all been there?

Lying awake, telling ourselves ‘don’t think about it’, only to find the thought returning with more menace.

It feels almost unfair, as if the mind is playing tricks on us.

In psychology we have a name for this (of course!): ironic process, which explains why trying not to think about something often makes us think about it more.

How the Mind Protects & Backfires

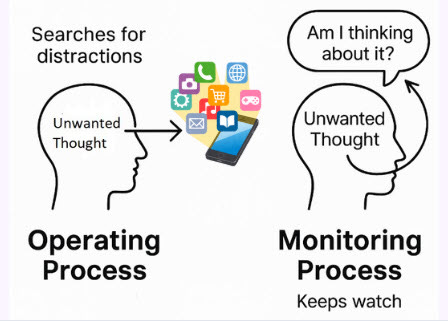

When we try to push a thought away, the mind sets up two systems. The first is what Daniel Wegner called the operating process [1]. This is the part that goes searching for distractions, anything else to think about so the unwanted thought stays out of view.

But the mind does not stop there, because it’s designed to keep us alert to what’s relevant or threatening. So, alongside the operating process it runs a second system: the monitoring process. Its job is to keep watch, to scan for the very thought we are trying to avoid, almost like a guard checking the gates. This double-checking is meant to protect us, but it ends up doing the opposite and the thought is repeatedly brought to the surface!

That is what my nephew was experiencing late that night. The harder he tried to stop thinking about what bothered him, the more he was reminded of it.

His mind was doing exactly what minds do when we try to suppress a thought.

Don’t Think of a White Bear!

One of the most well-known demonstrations of the ironic process is what became known as the “white bear” experiment [2]. Here, Daniel Wegner and his colleagues asked participants to verbalise their thoughts for five minutes while avoiding any thought of a white bear.

However, participants were told, if a white bear came to mind, ring a bell. Despite clear instructions to suppress the thought, participants rang the bell several times reporting emerging thoughts of a white bear.

After a while, the same participants were told by the researchers that they could think about anything they liked (no suppresion of anything). Guess what? White bear thoughts appeared even more often! This rebound effect showed that suppression not only fails in the moment, but it can also make the thought more persistent afterward!

The lesson here is pretty straightforward. The monitoring process keeps the unwanted thought active in our mental landscape, making its return more likely once the operating process stops.

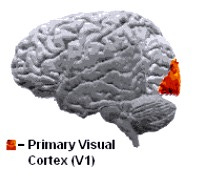

Recent neuroimaging research has supported the white bear experiment rationale, by demonstrating that even when individuals report successfully suppressing a thought, neural patterns linked to it can still be decoded in the brain’s visual areas [3].

In other words, suppression does not eliminate the thought, it only conceals it from awareness.

Keeping the Problem Alive

Now, if the white bear experiment shows us what happens in a controlled lab setting, things get even more complicated in daily life. See, under stress or mental load, the effects of suppression become even stronger (Have you noticed how it’s often when we most need calm that our minds seem least willing to give it?).

Research supports this as well. A 2020 meta-analysis confirmed that suppression fails frequently. It concluded (once more) that unwanted thoughts tend to rebound, and when the mind is under stress or cognitive strain, they can break through even faster [4].

And this is not just about harmless images like white bears. When people tried to push away painful memories or difficult emotions, suppression often backfired, making what they were trying to avoid even more persistent; not just in general but clearly under emotional strain [5].

In everyday life, this means the quick fix of “just don’t think about it” can end up keeping the problem alive.

That night on the phone, my nephew was learning this first-hand. The more tired he became, the harder he tried to force the thought out, and the more it circled back.

The stress of wanting to rest, of wanting a break only fuelled the loop.

Speaking the Thought

So I asked him to tell me very clearly what kept circling in his mind.

Rather than pushing the burdensome thought away, we gave it words and spoke about it directly: what it meant, why it kept returning, and what it revealed about him and the situation.

Our talk didn’t erase or solve the situation there & then, but it broke the cycle of suppression by allowing the thought to be addressed instead of fought.

That was enough for him to find some rest that night. And it’s often enough for us, too: not to defeat a thought, but to understand why it insists on being heard.

Did you know I’ve written a book? ༄˖°.☕️.ೃ࿔📚*:・

It’s called What Makes a Resilient Mind? If you’re curious, you can find it on Amazon.

Reference List:

[1] Wegner, D. M. (1994). Ironic processes of mental control. Psychological Review, 101(1), 34–52. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.101.1.34

[2] Wegner, D. M., Schneider, D. J., Carter, S. R., & White, T. L. (1987). Paradoxical effects of thought suppression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(1), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.53.1.5

[3] Koenig-Robert, R., & Pearson, J. (2021). Decoding nonconscious thought representations during successful thought suppression. Cerebral Cortex, 31(2), 1053–1062. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhaa255

[4] Wang, D., Hagger, M. S., & Chatzisarantis, N. L. D. (2020). Ironic effects of thought suppression: A meta‑analysis. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(3), 778–793. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691619898795

[5] Burns, J. W., Quartana, P., Gilliam, W., Gray, E., & Matsuura, J. (2008). Effects of anger suppression on pain severity and pain behaviors among chronic pain patients: Evaluation of an ironic process model. Health Psychology, 27(2), 238–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.238

I found this post really interesting Dom. In terms of trauma, although I desperately wanted to get away from revisiting really difficult memories after my son died, my mind kept taking me back there. I realised that, at some point, I would have to revisit them INTENTIONALLY. Only then (because this would involve difficult but necessary processing) would I be free of them.

Previous to this I’d had well-meaning friends telling me they wanted me to stop feeling guilty. I told them I shared this desire…but that it wasn’t that easy! Because of course I still experienced my mind as a threat (not my friend) Your words show why:

But the mind does not stop there, because it’s designed to keep us alert to what’s relevant or threatening.

Only by making friends with the workings of my mind (back to that old chestnut, self-compassion) was I able to stop the destructive thinking loop.

With much relief, and thanks in no small part to the compassionate space offered by other Substackers, I can say with confidence that I have.

I continue to find your writing on here immensely helpful in understanding and plotting my progress, thank you 🙏 😊

Whilst I was reading your post the white bear kept appearing.