Why Bad Memories Last Longer: A Cognitive Science Exploration

Inside the Mind’s Bias for Negativity

We all carry a collection of memories with us; some warm and joyful, others painful and hard to shake. And speaking of hard to shake memories, have you noticed how negative memories tend to be a bit more, well… stickier than the positive ones?

Recent (2024) research by Imaobong Olsson sheds light on why negative memories are often more vivid, persistent, and impactful than positive memories, providing insights that can help us better understand our emotional lives and why some experiences linger longer than others.

Bias & Survival

I trust you’ve heard of a psychological phenomenon called the “negativity bias.” Negativity bias influences both what we notice (attention) and what we remember (memory). Like when you quickly notice a single critical remark in a conversation at work, and find yourself replaying it in your mind long after many positive comments had been shared.

That’s negativity bias in action.

A cruel phenomenon indeed!

But evolution offers some solace: it helped keep us alive. For our ancestors, clear and vivid memories of threatening, harmful experiences was crucial for survival. So the brain evolved structures and mechanisms that prioritise negative memories to help us avoid danger and stay alive.

Brain regions such as the amygdala and hippocampus are crucial here.

Very simply put, the hippocampus plays a key role in the formation and consolidation of experiences (both positive and negative). The amygdala works in parallel to support this formation and consolidation, and because its activity is stronger during emotionally arousing experiences, it enhances memories tied to those events, enabling us to learn from them so we can avoid similar harm in the future.

This mechanism proved to work pretty well for survival, but as with all good things, there is a cost: to this day, negative memories get ‘VIP’ treatment in our minds, becoming more striking, detailed, and harder to forget.

As for the positive ones, while very important indeed, they don’t demand the same urgent attention and so tend to remain in the background.

Mental Rehearsal

So, when an event is emotionally impactful, our nervous system kicks into high gear, heightening emotional intensity and attention during the experience. This leads to deeper encoding of threatening or harmful events, resulting in memories we recall more vividly and in a biased way.

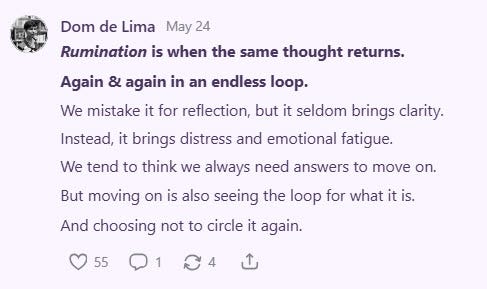

To add insult to injury, the emotional weight of negative memories ( i.e. unresolved feelings or perceived threats to the self) lends itself to another unfavourable psychological phenomenon: rumination.

That is why we tend to mentally rehearse and replay these events in our minds. But in doing so, we inadvertently strengthen their persistence and emotional impact. Meanwhile, and once again, positive memories just sit back because they don’t threaten the self or signal pressing problems.

There are wider consequences to this.

How Our Memories Keep Past Experiences Alive

The memory feels heavy and somewhat constricting, as if the disappointment is lingering. This memory often comes to mind with vivid details, such as the wording of the rejection email and my immediate reactions — Participant 2, p. 32

While negative experiences themselves hold significant emotional weight, it’s the memories of the events (how we recall and interpret them) that continue to influence our lives long after the moment has passed.

Participants in Olsson’s study described negative memories that went beyond simple recollection. Memories which carried profound personal meaning and often held emotional weight that extended far beyond the original event.

This ongoing relationship between memory and our present highlights how our inner world is deeply connected to the stories we tell ourselves about our past. Our memories don’t just exist in bygone times; they actively shape how we navigate relationships, make decisions, and respond emotionally to new situations.

In this way, memory becomes a living thread weaving our past experiences into the present fabric of our lives.

What This Means for Us

Understanding why negative memories linger longer than positive ones can foster psychological wellbeing, as it explains why certain feelings stick with us, sometimes making it hard to move on or feel balanced.

Instead of blaming ourselves for “holding on” or “feeling stuck”, we can see these persistent memories as part of how our minds naturally work to protect us and help us learn from our experiences.

This awareness also opens doors to practical insights for coping.

We can intentionally develop strategies to tackle mechanisms like rumination, which we’ve seen contributes to negative memories becoming more deeply ingrained. It follows that the more you rehearse a negative memory, the more it will stick around.

Do keep in mind, that when it comes down to intrusive thoughts and rumination, once you notice it, it’s not just about turning off a switch (rumination: on/off). The skill here is learning not to allow negative mental events to take over.

So, notice the loop and choose not to circle around it again. Over time, this helps weaken the hold that negative memories and rumination have on you, allowing you to regain a sense of calm and control.

Concluding Thoughts

Our minds are wired to remember the negative more vividly and for longer than the positive, a mechanism rooted in survival and shaped by complex neural mechanisms. While it helped our ancestors learn from danger and avoid future harm, it also means certain painful memories can linger, influencing how we see ourselves and navigate the world long after the event has passed.

Understanding this natural tendency can bring compassion towards ourselves when difficult memories or feelings persist. Rather than seeing these experiences as personal failings, we can recognise them as part of how our minds protect and teach us.

So, as you reflect on your own memories, consider this: Which ones shape your story?

Reference List:

Olsson, I. J. (2024). Exploring the persistence of negative emotional memories over positive ones: A qualitative study. International Journal of Psychological Studies, 16(4), 26–26. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijps.v16n4p26

Note from Dom (PTSD):

This article and Olsson’s study focus on typical negative memories, not traumatic ones. In PTSD, memory systems can become dysregulated in several ways. For example, altered function at the molecular level and in hippocampal neural circuits, as well as impaired executive functioning. This often results in hypervigilance, re-experiencing, dissociation, and impaired contextualisation, which differ fundamentally from how negative memories are usually encoded and recalled [1].

Reference:

[1] Brzozowska, A., & Grabowski, J. (2025). Hyperarousal, dissociation, emotion dysregulation, and re-experiencing—Towards understanding molecular aspects of PTSD symptoms. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(11), 5216. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26115216

I do not think it is possible to "develop strategies to tackle mechanisms like rumination". It's my experience at least that it is entirely impossible to control what one thinks about in the way that would be helpful.

We can direct to some degree what we are actively thinking about, but whether or not it will encompass the brain so completely as to effectively cease the thoughts we ruminate on is another matter.

I am not saying it isn't worth the effort. Only that for me, my thoughts choose when and where they show themselves at the forefront of my thinking, leaving me to either engage or be swept away.

And the contrarian in me is screaming into my ear that somehow this would be, in a real way, an act of lessening how much we care about the events that reside with us so strongly. For some kinds of memories this may be ideal, but for most of mine, it would be like saying someone or something I care about, and have lost, no longer matters as much.

That is something I cannot, and will not abide. If the cost of giving value to those precious few things that to this day remind me of their being gone or lost is the darkness that claims me for weeks at a time, so be it.

So, in totality, I think perhaps it's a better direction to work on coping skills like understanding and accepting the rules and limitations of life as we know it, the universe, and that it's part of having something to lose it eventually. Nothing is forever.

Perhaps that would have a chance at helping some, even if it doesn't help me very much.

*Disclaimer for anyone else who might ready this comment* I am in a very dark place currently, so if my comment appears overly dramatic or dark in nature, please try to take only the message, and not the tone.

Dom - Thank you for this thoughtful dive into why negative memories linger. It's a helpful reminder here as you relay that our brains are trying to protect us, doing what they evolved to do. But what once kept us safe can now keep us stuck.

The insight that we can choose how we relate to these memories is powerful. And while we can’t erase the negativity bias, we can offset it. On short quick example., would be pausing to truly savor positive moments by holding them in awareness for just 10–20 seconds. This helps the brain encode them more deeply. Over time, this simple practice can help us rebalance how we remember, helping us live more vibrantly around the positive.